DISAPPEARED FOR 5 YEARS

STUDYING THINGS I’VE NEVER SEEN

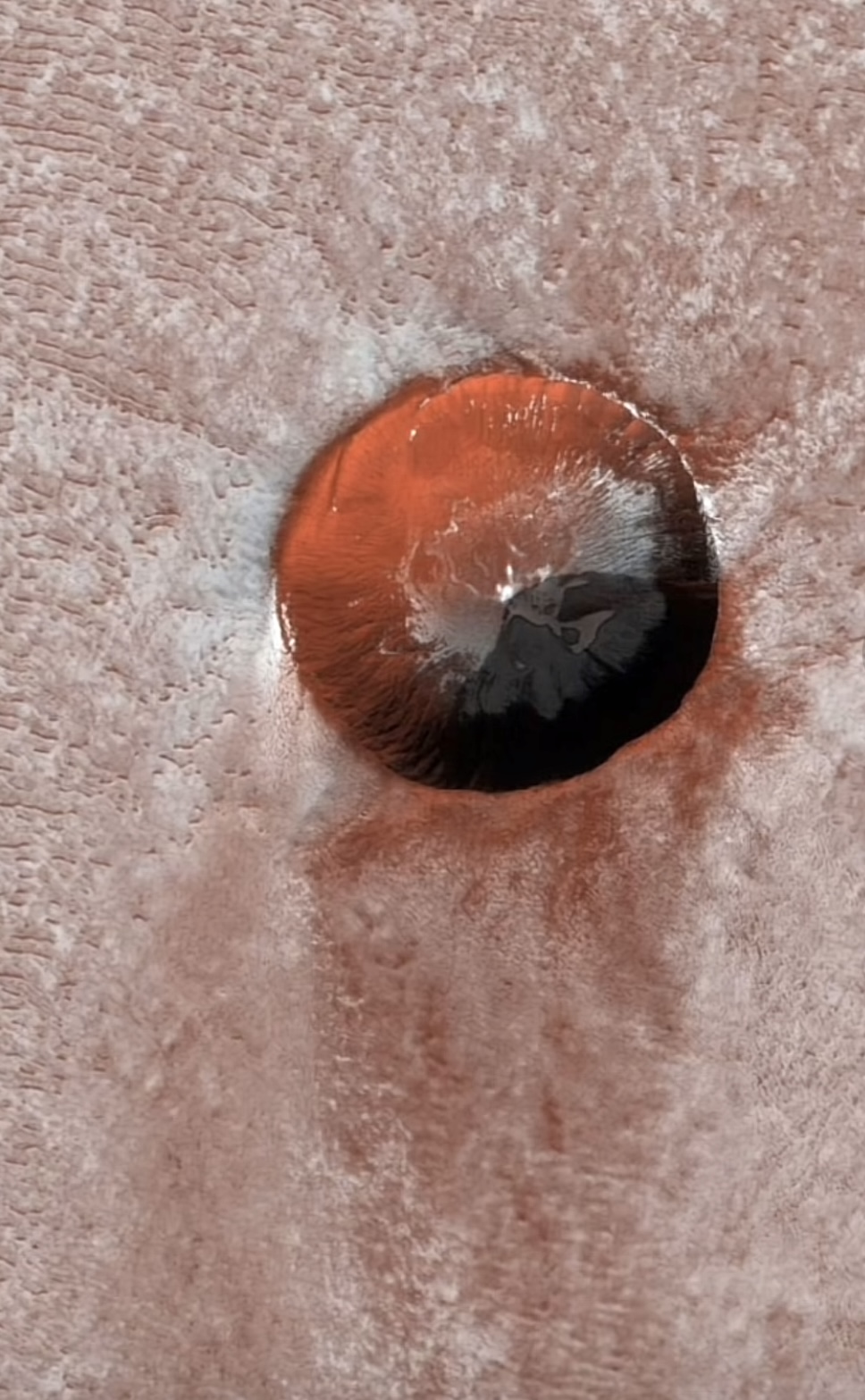

KAREZ

QANAT

FALAJ

[But now I’m back

+ someday]

“Qanats milk the earth while deep wells suck earth blood”

Truth has weight. If we consider substance, water, Truth becomes unavoidable.

Couldn’t get into any of this, and I didn’t throughout my studies. The work is practical, it will stay that way.

But now I can admit it, I was always distracted. Reading about the mechanics and the social infrastructure of the qanat made it difficult for me not to think about Tawhid, Abubakr Mohammad Karaji’s The Extraction of Hidden Waters, Whitehead’s ideas about bodily sensation and causal transmission, prehension, conceptual reversion, and the ingress of novel propositions as the origin for evolutionary processes / Schelling’s discussion of interior/exterior ecologies, or dynamic polarities unified in the Absolute, Kant’s 12 “pure” concepts, and, yes you know, Negarestani’s ()hole complex.

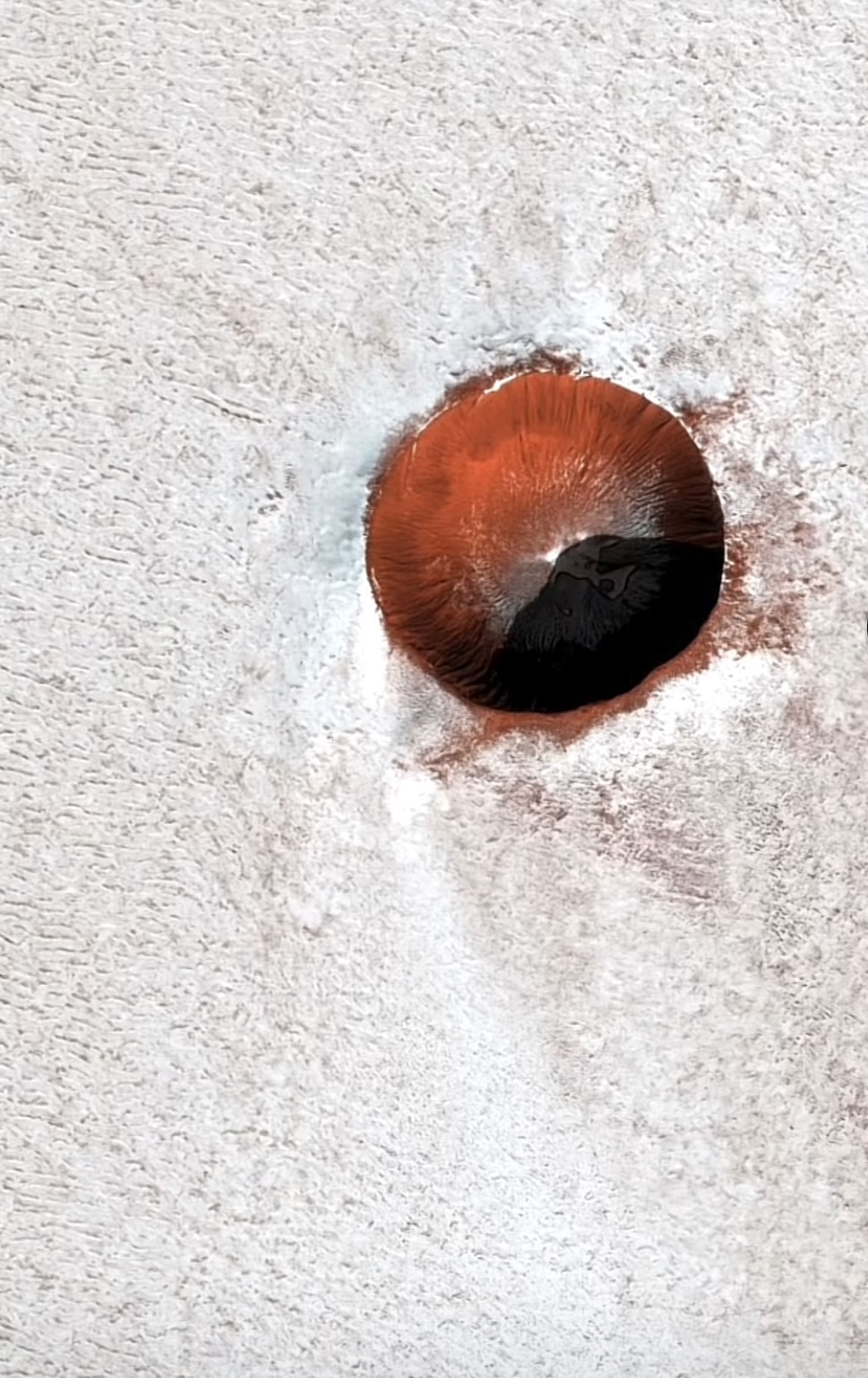

This idea that the universe works mechanistically toward beauty, aesthetic beauty, alright, I don’t know about that. I cannot corroborate this. But I like Whitehead’s ideas about bringing conflict into contrast: intensity (the foundation of beauty) is achieved through simultaneously holding as many contrasts as is possible. Who was so ‘myriad-minded,’ the progenitor, that they blended oppositions to such a degree that the original qanat was born over 3,000 years ago? They had to start by valuing barrenness and aridity deeply enough to transform it.

------------------------------------------------------

"... Schelling is not asserting this organic conception of nature as a regulative principle. The organizing principle which grounds natural organization is an objective entity. Moreover, Kant’s system of ends must bottom out in some unconditioned final end, which must, because it is unconditioned, be external to nature. For Kant, this is the human being under the moral law. Schelling’s difference in terminology—calling nature an organism rather than a system of ends—indicates a substantive philosophical difference. Nature, for Schelling, is not teleologically grounded in an external end, but rather is its own end, much like an organism. Schelling refers to nature as “a whole that is in-itself complete [ein in sich selbst vollendetes Ganzes].” Like an organism, it is cause and effect of itself. This self contained completion is in contradistinction to Kant’s externally dependent and directed nature. It is noteworthy that Schelling’s formulation universal organism is paradoxical in the context of Kant’s philosophy: organisms are grounded in particular forms of organization, mechanism is that which is universal. Schelling is drawing these together in the claim that the highest kind of organization is universal in scope—it subsumes all of nature—but also unitary and particular—it is an organism." --N. Fisher

------------------------------------------------------------

“In ()hole complex, on a superficial level (bound to surface dynamics), every activity of the solid appears as a tactic to conceal the void and appropriate it, as a program for inhibiting the void, accommodating the void by sucking it in to the economy of surfaces or filling it.”

“Once nemat-space begins its infestation, the periphery on the zone of excitations does not necessarily start from visible surfaces on the crust: Active surfaces emerge from everywhere, from the surface-crust mode of periphery to innermost recesses. The ()hole complex carves ultra-active surfaces from solidus when it digs holes, unleashes delirious itinerant lines and constructs its nematical machines, installing peripheral agitations on the surfaces it cuts from internal solid matrices. Everywhere a hole moves, a surface is invented. When the despotic necrocratic regime of periphery-core, for which everything should be concluded and grounded by the gravity of the core, is deteriorated."

---------------------------------------------------------

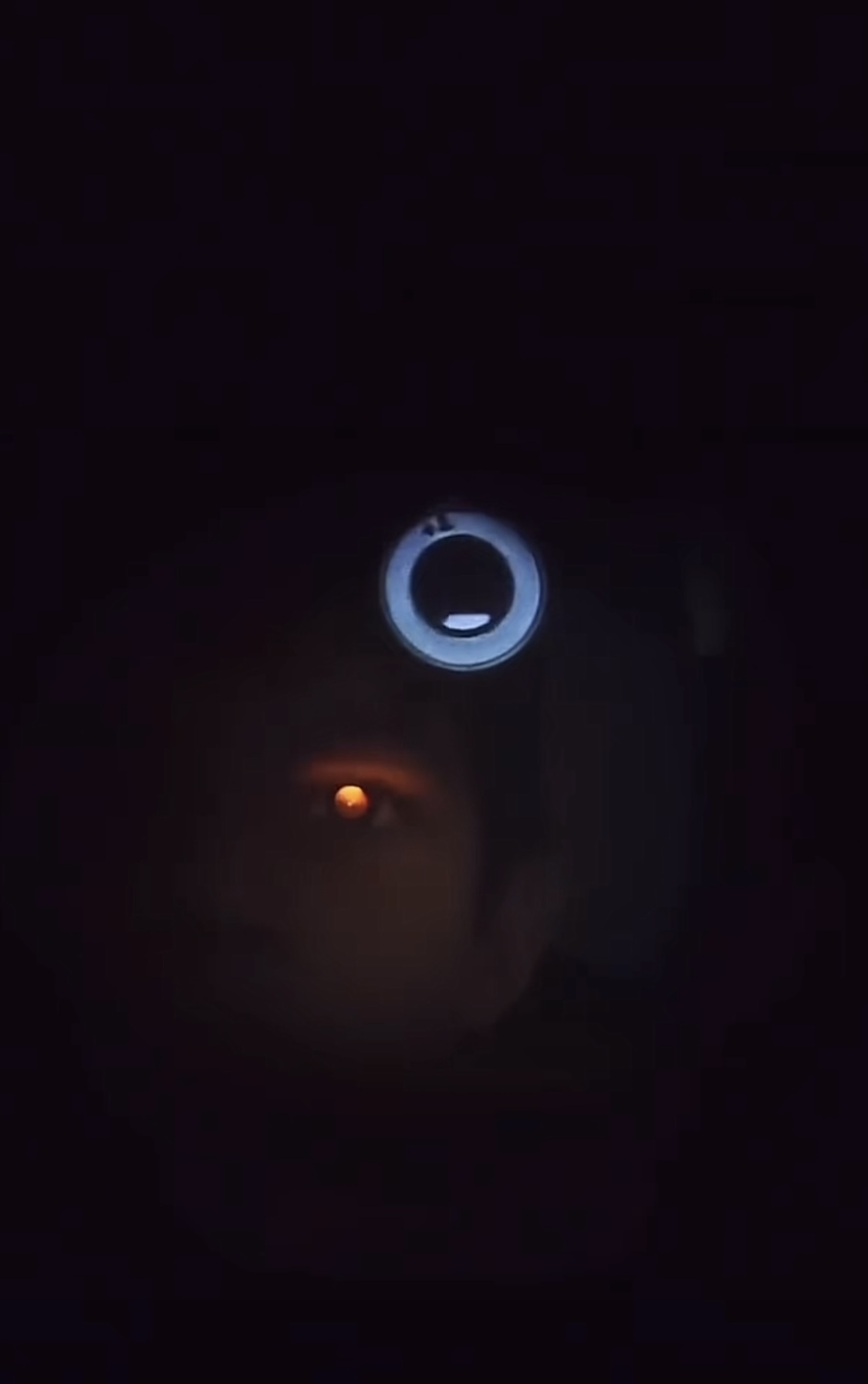

"Mohammed Hassan related a saying that at the rise of a star you can feel a breeze on your face for a

moment,– so you do not even need to see the star to know it has risen. There is also a saying that

when all is frozen, Suhayl has struck (risen), and their babies may urinate blood. This star is said to

rise in the east but to set a bit off west, which does not fit with the usual (literary) identification of

Suhayl as Canopus (α Carinae), which rises SSE." --Nash

------------------------------------------------------------

Category V.: The Category of Conceptual Reversion

There is secondary origination of conceptual feelings with data which are partially identical with, and partially diverse from, the eternal objects forming the data in the primary phase of the mental pole; the determination of identity and diversity depending on the subjective aim at attaining depth of intensity by reason of contrast.”

“… Then in synthesis, there must always be a ground of identity and an aim at contrast. The aim at contrast arises from the depth of intensity promoted by contrast. The joint necessity of this ground of identity and an aim at contrast. The aim at contrast arises from the depth of intensity promoted by contrast. The joint necessity of this ground of identity, and this aim at contrast, is partially expressed in this Category of Conceptual Reversion. This ‘aim at contrast’ is the expression of the ultimate creative purpose that each unification will achieve some maximum depth of intensity of feeling, subject to the conditions of its consecrescence.”

“An enduring object gains the enhanced intensity of feeling arising from contrast between inheritance and novel effect, and also gains the enhanced intensity arising from the combined inheritance of its stable rhythmic character throughout its life-history. It has the weight of repetition, the intensity of contrast, and the balance between the two factors of the contrast. In this way, the association of endurance with rhythm and physical vibration is explained. They arise out of the conditions for intensity and stability. The subjective aim is seeking width with its contrasts, within the unity of a general design. An intense experience is an aesthetic fact, and its categoreal conditions are to be generalised from aesthetic laws in particular arts.”

“God and the World are the contrasted opposites in terms of which Creativity achieves its supreme task of transforming disjoined multiplicity, with its diversities in opposition, into concrescent unity, with its diversities in contrast. In each actuality, there are two concrescent poles of realisation—‘enjoyment’ and ‘appetition,’ that is, the ‘physical’ and the ‘conceptual/For God, the conceptual is prior to the physical; for the World, the physical poles are prior to the conceptual poles.”

“Opposed elements stand to each other in mutual requirement. In their unity, they inhibit or contrast. God and the World stand to each other in this opposed requirement. God is the infinite ground of all mentality, the unity of vision seeking physical multiplicity. The World is the multiplicity of finites, actualities seeking a perfected unity. Neither God, nor the World, reaches static completion. Both are in the grip of the ultimate metaphysical ground, the creative advance into novelty. Either of them, God and the World, is the instrument of novelty for the other.”

“In every respect God and the World move conversely to each other in respect to their porcess. God is primordially one, namely he is the primordial unity of relevance of the many potential forms; in the process he acquires a consequent multiplicity, which the primordial character absorbs in its own unity. The World is primordially many, namely, the many actual occasions with their physical finitude; in the process it acquires a consequent unity, which is a novel occasion and is absorbed into the multiplicity of the primordial character. Thus God is to be conceived as one and as many int he converse sense in which the World is to be conceived as many and as one. The theme of Cosmology, which is the basis of all religions, is the story of the dynamic effort of the World passing into everlasting unity, and of the static majesty of God’s vision, accomplishing its purpose of completion by absorption of the World’s multiplicity of effort.”